RIBA Studio: courses in Architecture for students working in practice

The RIBA Studio is a unique programme for students in practice who are based all across the UK, EU, and EEA. Students work towards their registration as Architects in the UK, a title which now has mutual recognition agreements across Australia, Canada, and the US.

This practice-based route is designed to foster the critical skills for study and practice, and the knowledge and confidence to thrive in the profession. Students work one-to-one with a personal tutor and meet us online for workshop and milestone events during the development of their module work. We are a widening participation programme because of the range of mechanism in place to support practice-based students related to timing, multiple submissions and study leave.

Uniquely, students follow the subjects they are passionate about and interpret briefs to suit their personal interests, ambitions, and geographic and socio-political contexts. This is much valued by the practices who benefit from their student - employee input.

Our students compete for prizes against students in full time study and have won prestigious awards which is testimony to their commitment to learn and the drive to make an enduring positive impact to society through our profession.

For more information write to us at: ribastudio-applications@brookes.ac.uk

The RIBA Foundation is an entry point into the creative fields for anyone looking to develop their first portfolio and the skills to thrive in the next level of study.

Students are based all across the global and meet us regularly online for workshop and milestone submissions that serve to raise the sensibilities of architectural thinking. Through the practice placement, students gain a full understanding of what it means to be in practice and deepen their self- belief about their place and contribution within the creative fields.

For more information write to us at: ribafoundation@brookes.ac.uk

Highlights from the Foundation in Architecture

Emilia Jagiello - RIBA Studio Foundation

Personal tutor: Marianna Serra

A strong foundation is essential to any project, and this introductory architecture course offered the chance to develop my own ways of seeing and interpreting the world. Through a sequence of assignments which ranged from time and space organisation to broader global issues, I was encouraged to explore personal interests and respond to challenges through my own lens. Facing the blank canvas—both literally and conceptually—was often daunting, but it became a space for refining ideas while pursuing designs rooted in personal interests and lived experience.

Workshops running alongside the main projects expanded my skillset in unexpected ways. A personal highlight was experimenting with paper mechanics. Often associated with children’s pop-up books, it revealed itself as a powerful spatial and storytelling tool. Engaging with different materials and mediums, I found new ways to express ideas and see how they occupy space.

Curating the final portfolio became a reflective process in itself—connecting outcomes, shaping a narrative, and recognising growth over time.

These works mark the beginning of an ongoing exploration into architecture, materials, and the language of visual communication.

Assigning meaning through materiality

A game to calendarise

Creating the calendar through the process of play

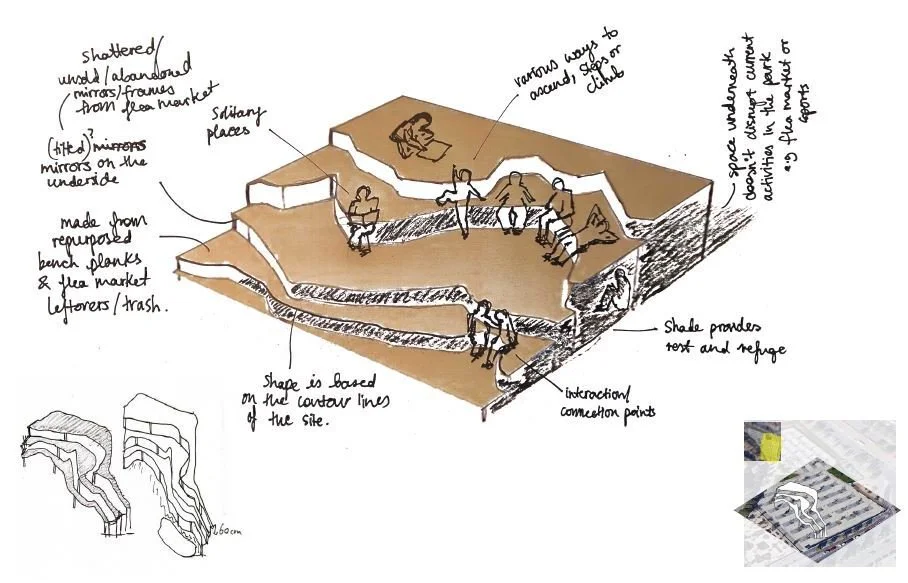

Pavilion concept development

Exploration of adaptive reuse and repurposing materials

Final render of proposed intervention

Paper mechanics and storytelling

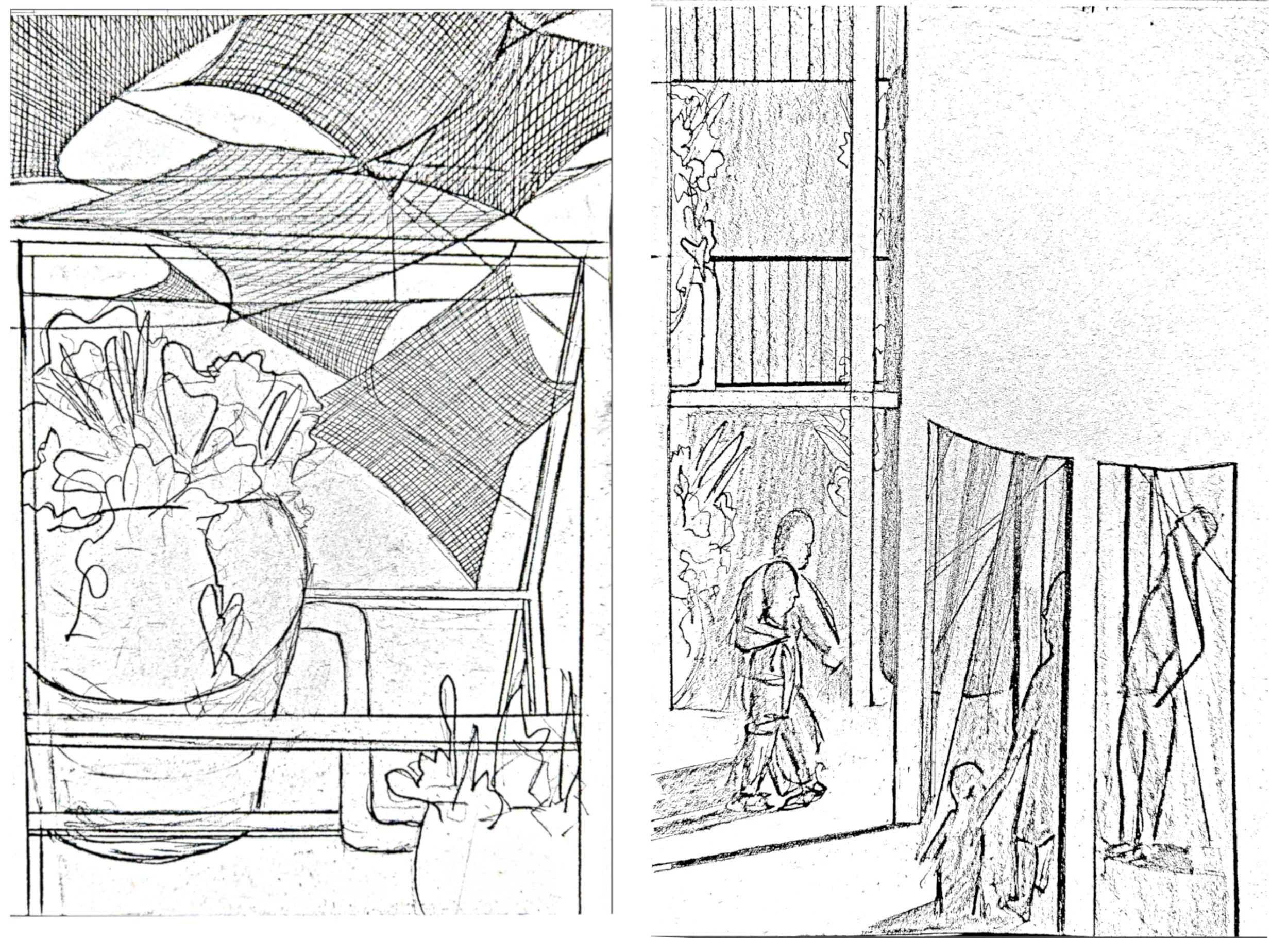

Reimagining exterior perspectives

Conceptual collage

Capturing visitor experiences

Highlights from the Foundation in Architecture

Em Aldridge - RIBA Studio Foundation

Personal tutor: Sam Whetstone

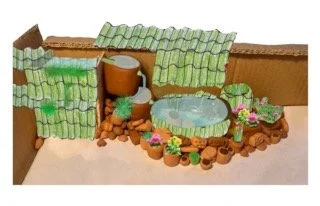

With increased deforestation, urbanisation and destruction of natural habitats, fragmentation of viable homes for wildlife is increasing at an exponential rate. Building of infrastructure and other changes to the topography of the land can produce physical barriers that prevent species movement, decreasing the population carrying capacity and in turn decreasing the diversity of species. This project aimed to explore how London’s “grey” gardens could be greened by its human inhabitants and through this, help to create green corridors between London’s green spaces. An idea supporting the London Wildlife Trust’s “Garden for a Living London” project.

The unexpected finding of a toad in Em’s concrete slab of a garden became the focus of the project. To breed a toad needs a pond to lay its egg and spend its first life stages, for this reason the creation of a pond became the main aim. Through experimenting with materials collected off the streets and from household waste Em explored how they could be used to make the concrete slab more of a home for the toad and how water could be collected to fill the pond.

Habitat Fragmentation

Pond

Pond integration

Pond Intervention

Pond

Uses of my garden

As Told by the Other

Jade Nembhard - RIBA Studio Foundation

Personal tutor: Johannah Fenning

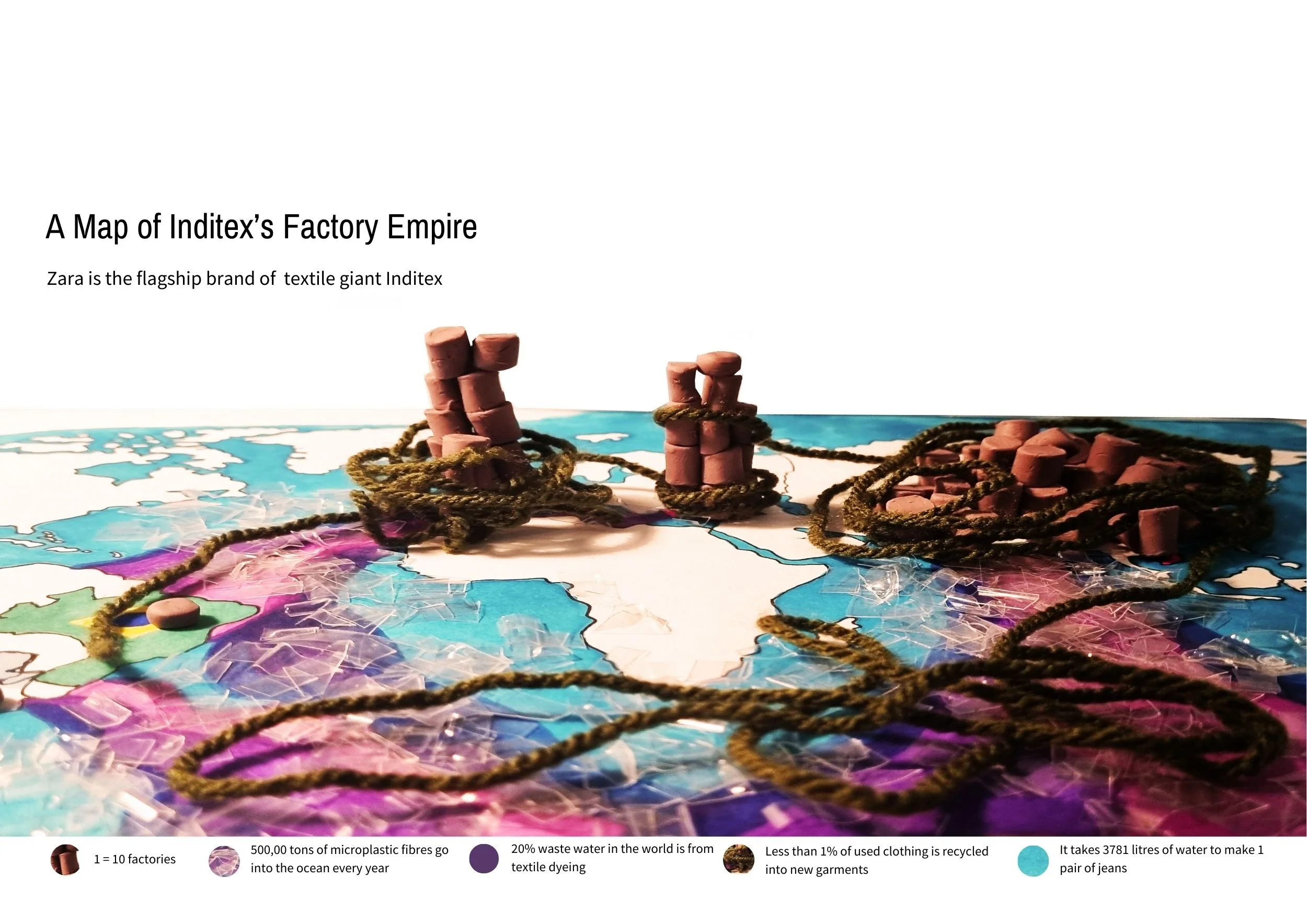

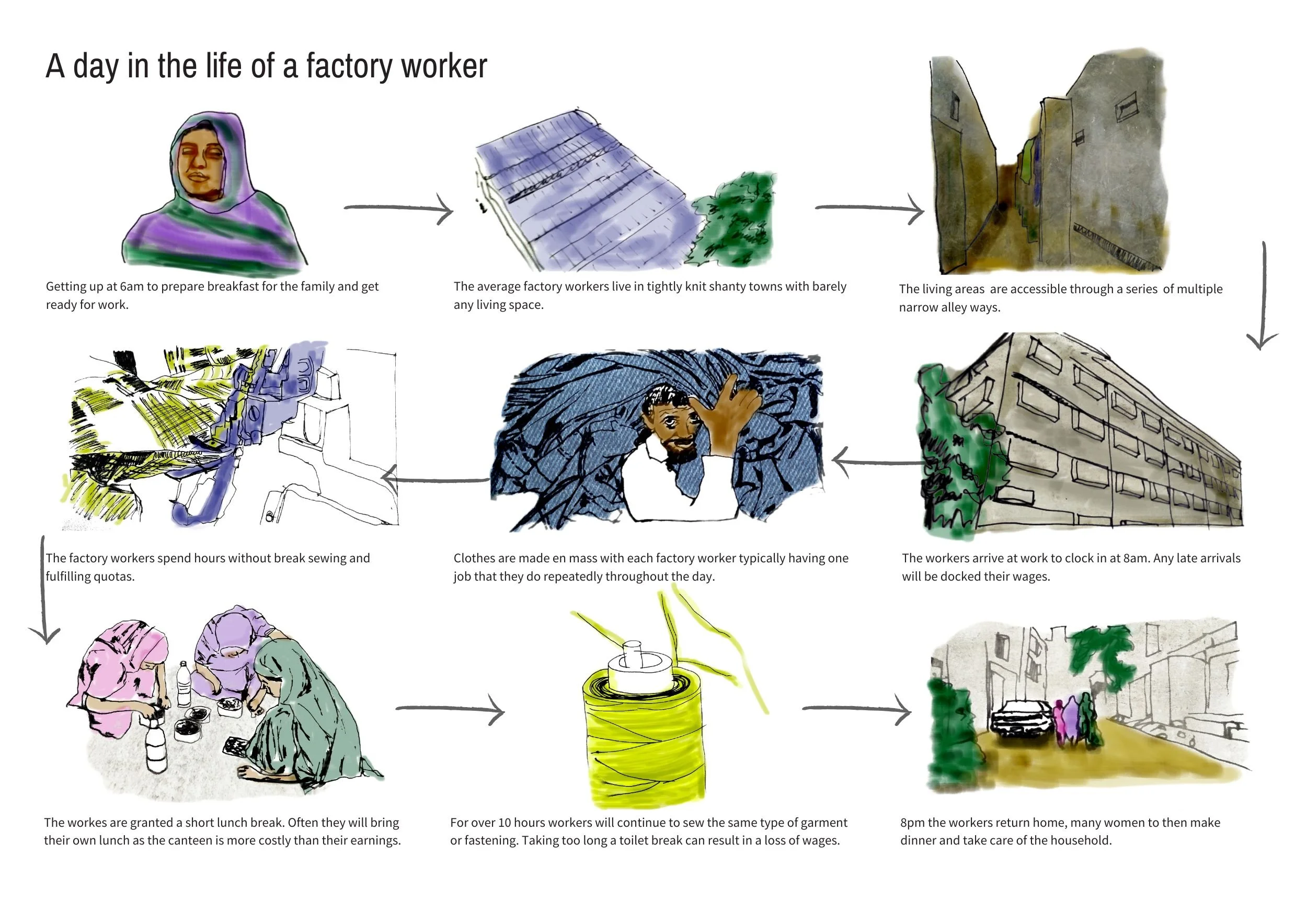

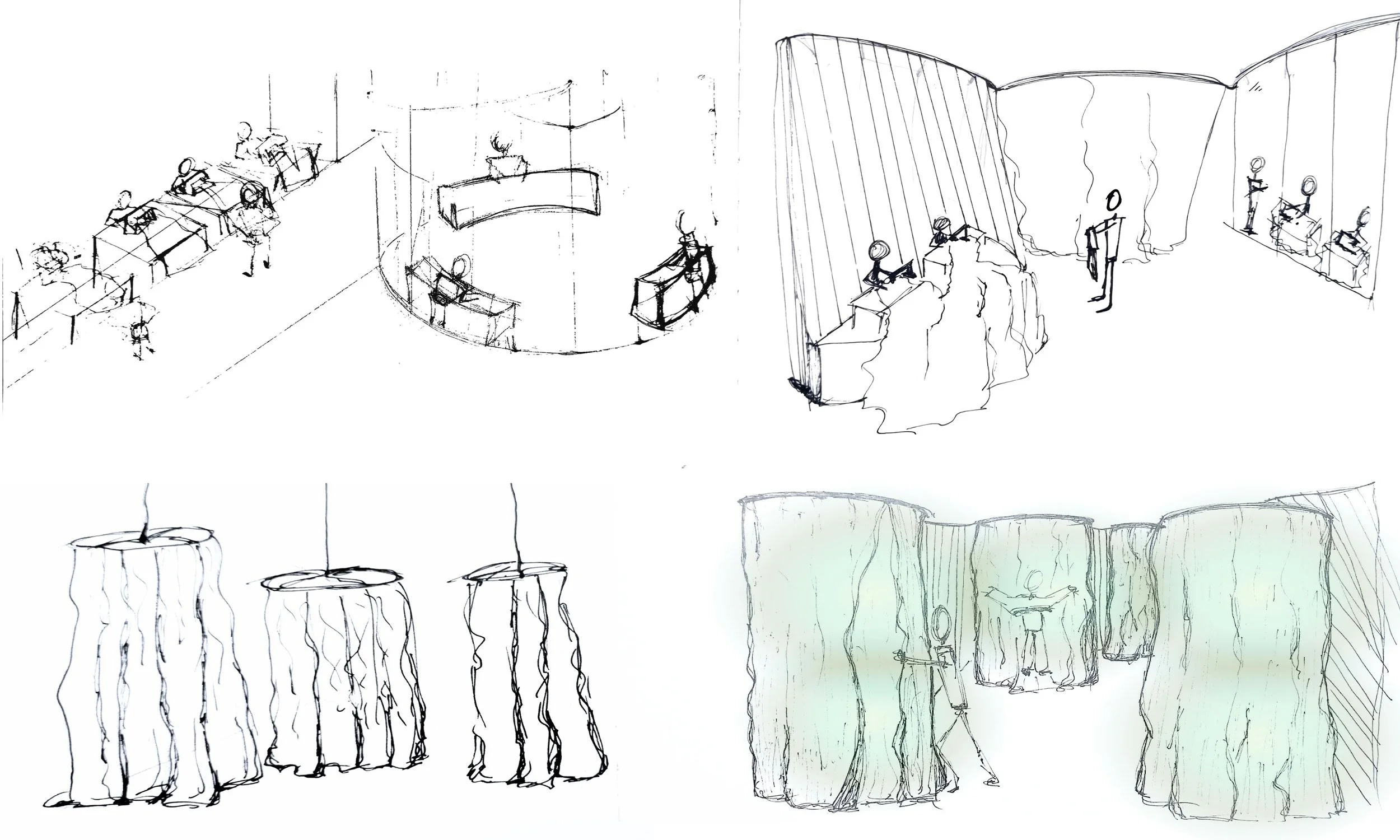

In this portfolio, I explore themes of home, belonging, community, and global responsibility from the perspective of those, including myself, who are often ‘othered’ in Western society. A key focus was immigration, particularly the Windrush Generation. I created an alternative view map to shift the narrative—highlighting what the Windrush Generation contributed to the UK, rather than reinforcing the idea that immigration takes something away from “native” residents. I also tackled the issue of Fast Fashion, a crisis that touches everyone. My aim was to confront Western consumerism by exposing the harsh realities faced by factory workers. I proposed an immersive intervention that transforms retail spaces into simulated factory environments, encouraging shoppers to reflect on the true cost of their purchases. For a local public green space intervention, I challenged the assumption that such areas need improvement. Instead, I explored the symbolic and physical implications of the fences and borders that surround them, questioning who is being kept in or out. Across each project, my goal was to disrupt dominant narratives and prompt critical reflection on inclusion, responsibility, and the systems we often take for granted.

Africa Map

PopUp Book

Factory Map

Mixed media fast fashion

Day in the life

Sketches

Model fashion

Shop

Fence Model

Fence in situ

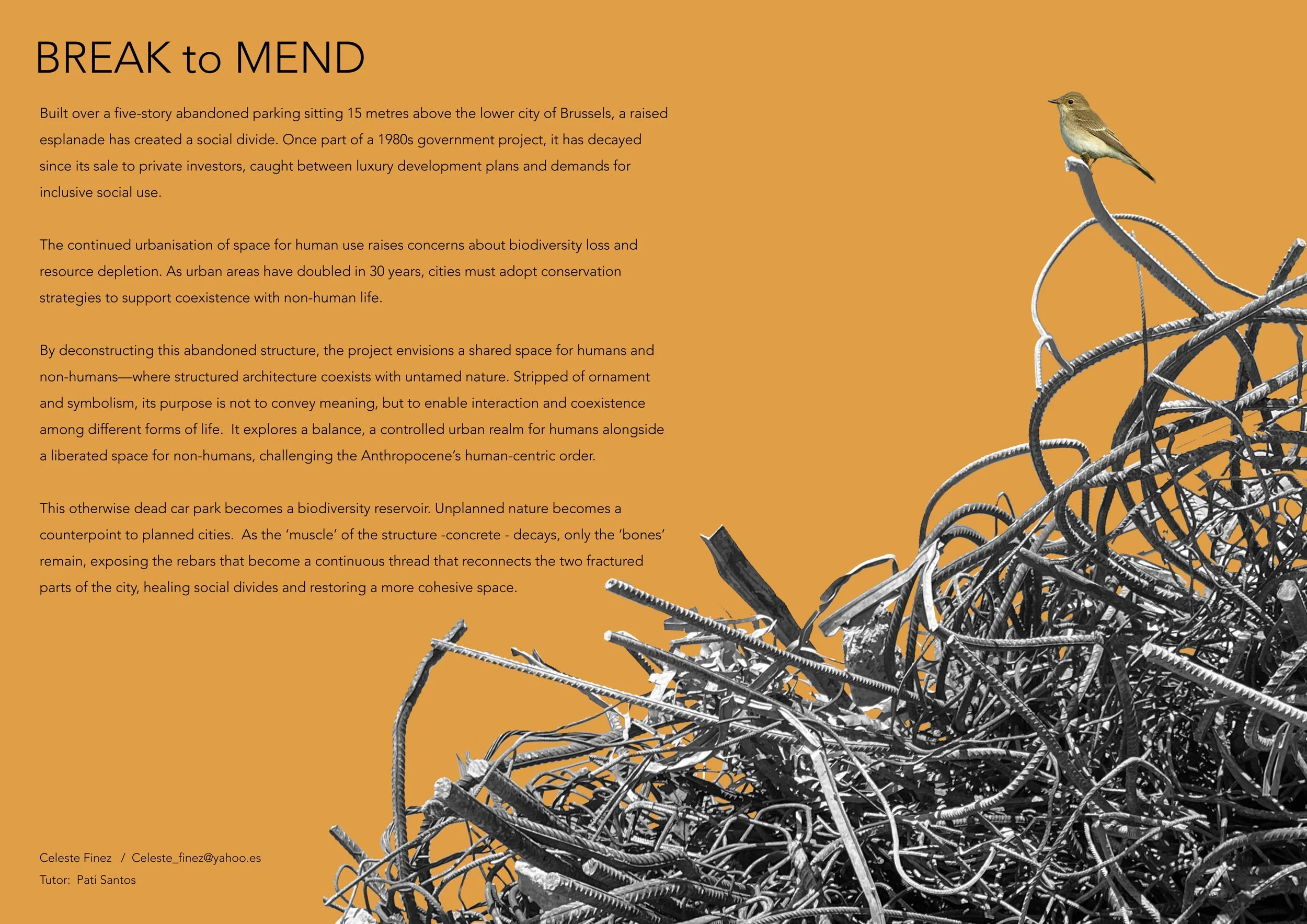

BREAK to MEND

Celeste Finez - RIBA Studio Certificate

Personal tutor: Pati Santos

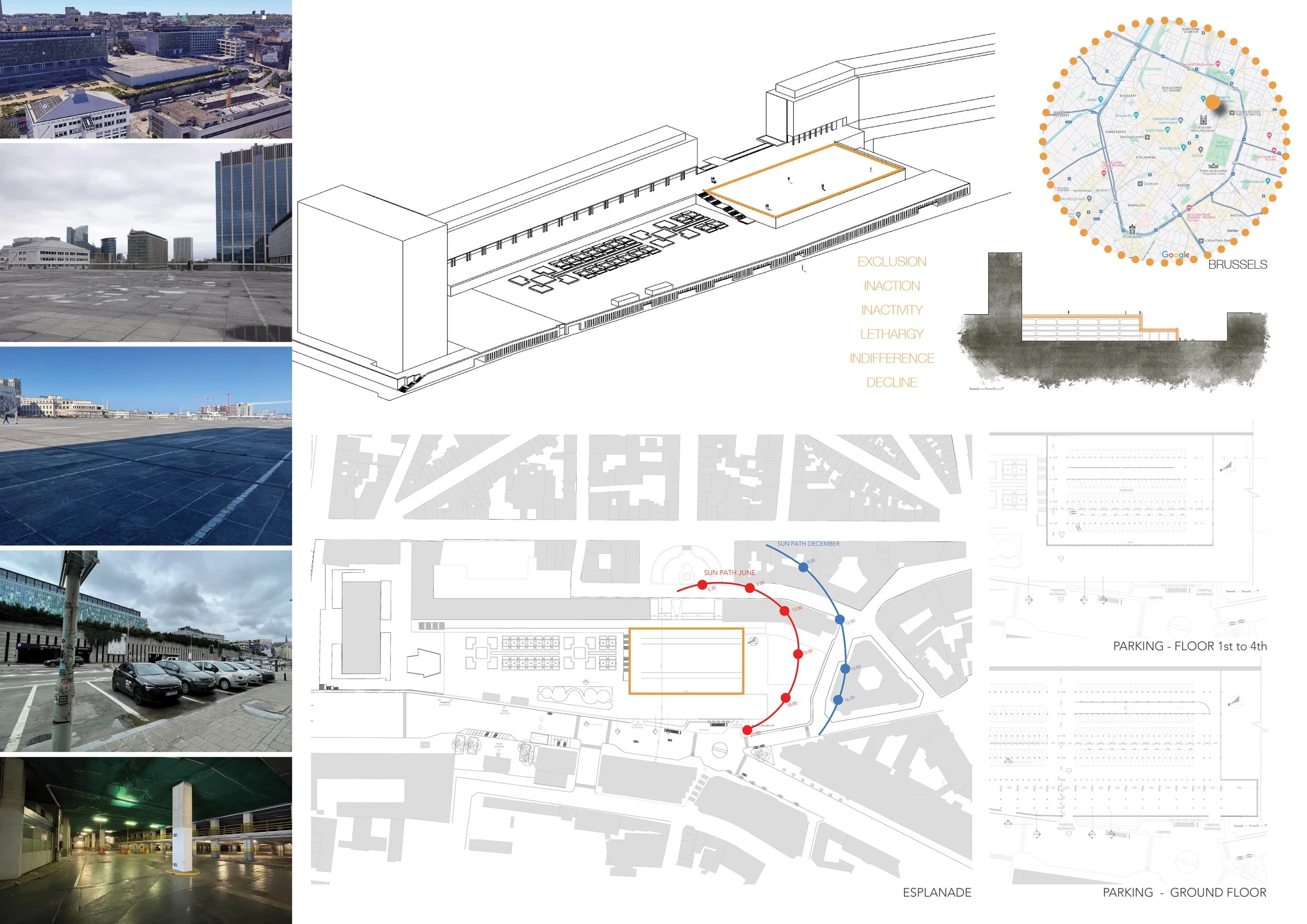

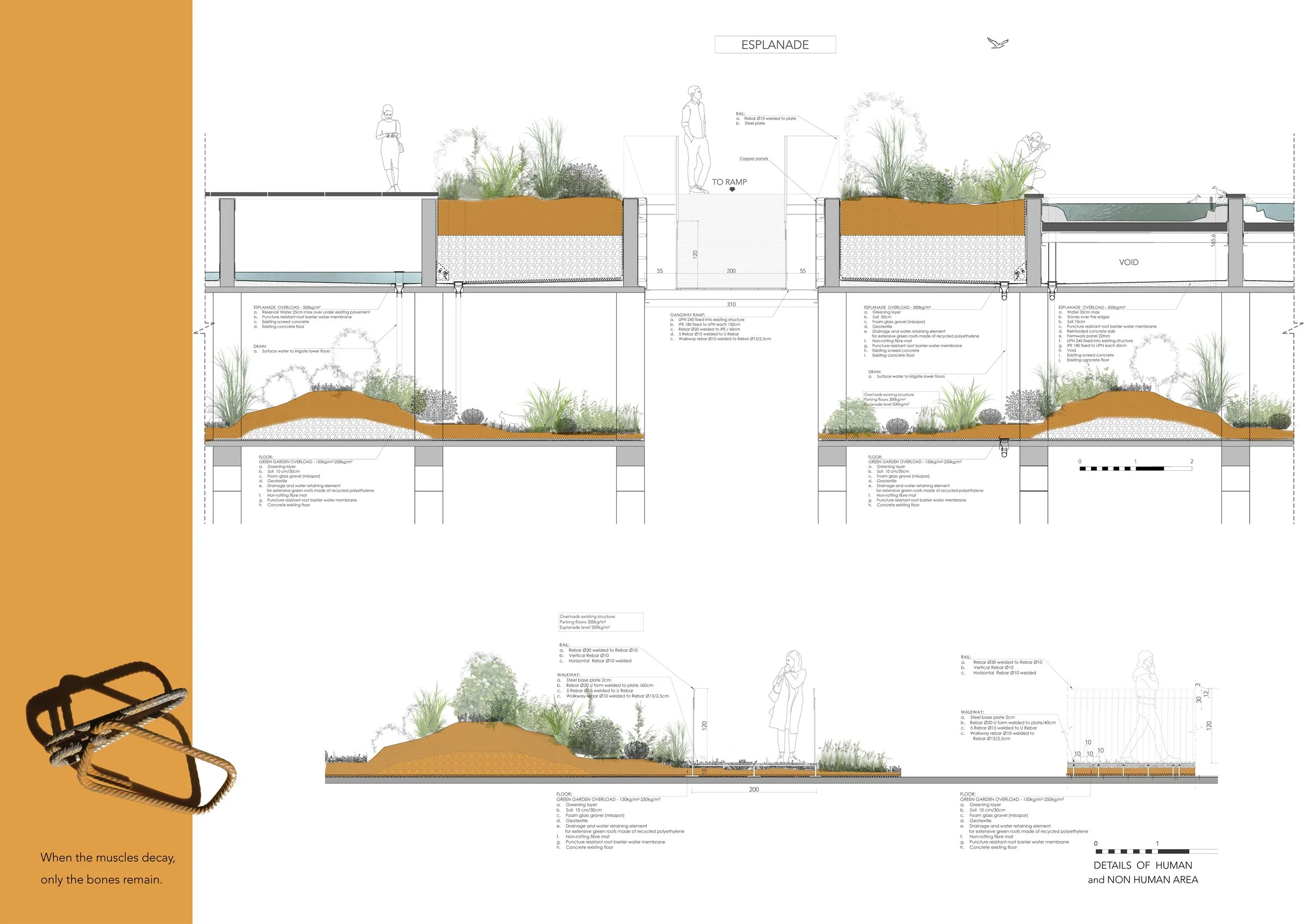

Built over a five-story abandoned car park sitting 15 metres above the lower city of Brussels, a raised esplanade has created a social divide. Once part of a 1980s government project, it has decayed since its sale to private investors, caught between luxury development plans and demands for inclusive social use.

The continued urbanisation of space for human use raises concerns about biodiversity loss and resource depletion. As urban areas have doubled in 30 years, cities must adopt conservation strategies to support coexistence with non-human life.

By deconstructing this abandoned structure, the project envisions a shared space for humans and non-humans—where structured architecture coexists with untamed nature. Stripped of ornament and symbolism, its purpose is not to convey meaning, but to enable interaction and coexistence among different forms of life. It explores a balance, a controlled urban realm for humans alongside a liberated space for non-humans, challenging the Anthropocene’s human-centric order.

This otherwise dead car park becomes a biodiversity reservoir. Unplanned nature becomes a counterpoint to planned cities. As the 'muscle' of the structure -concrete - decays, only the 'bones' remain, exposing the rebars that become a continuous thread that reconnects the two fractured parts of the city, healing social divides and restoring a more cohesive space.

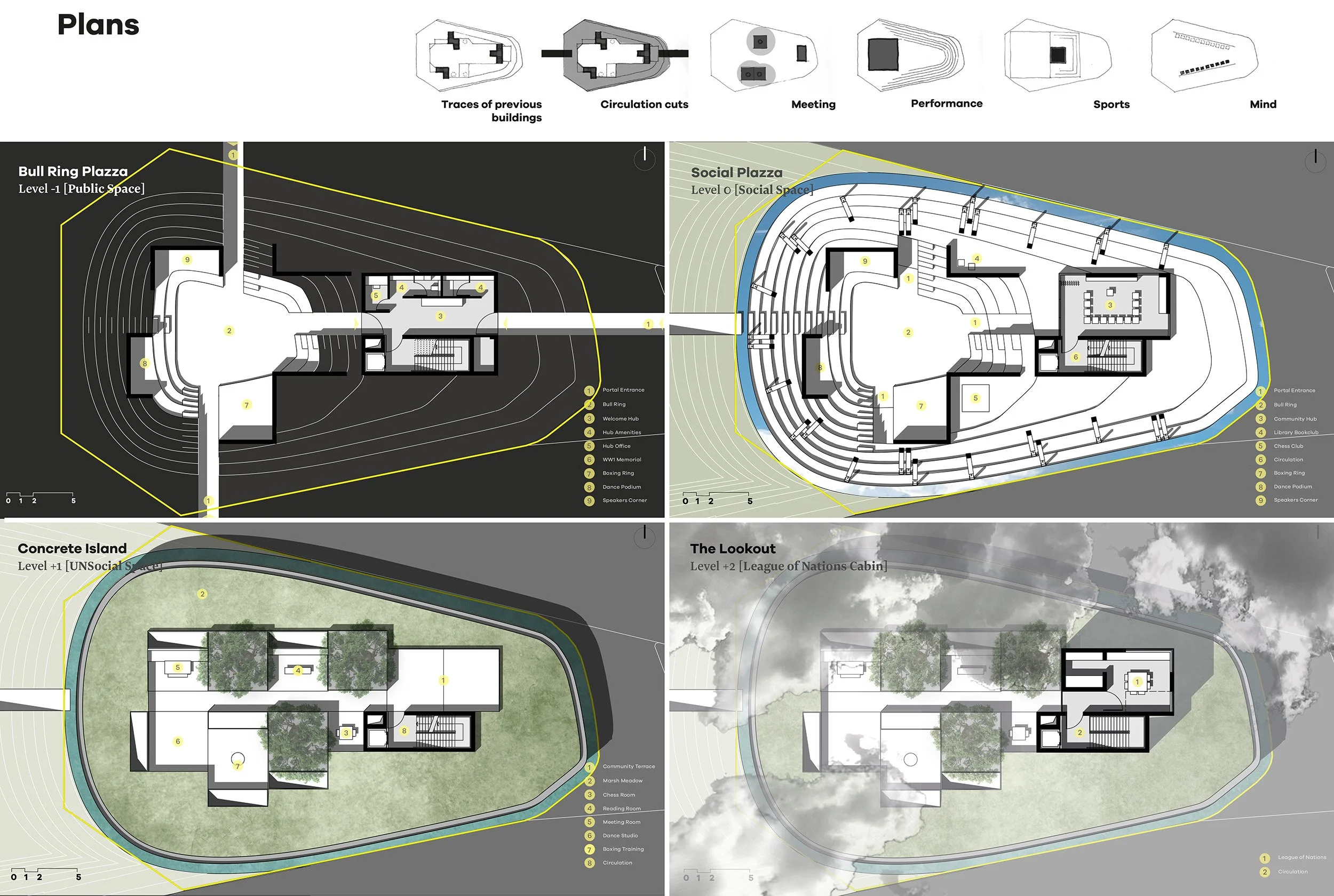

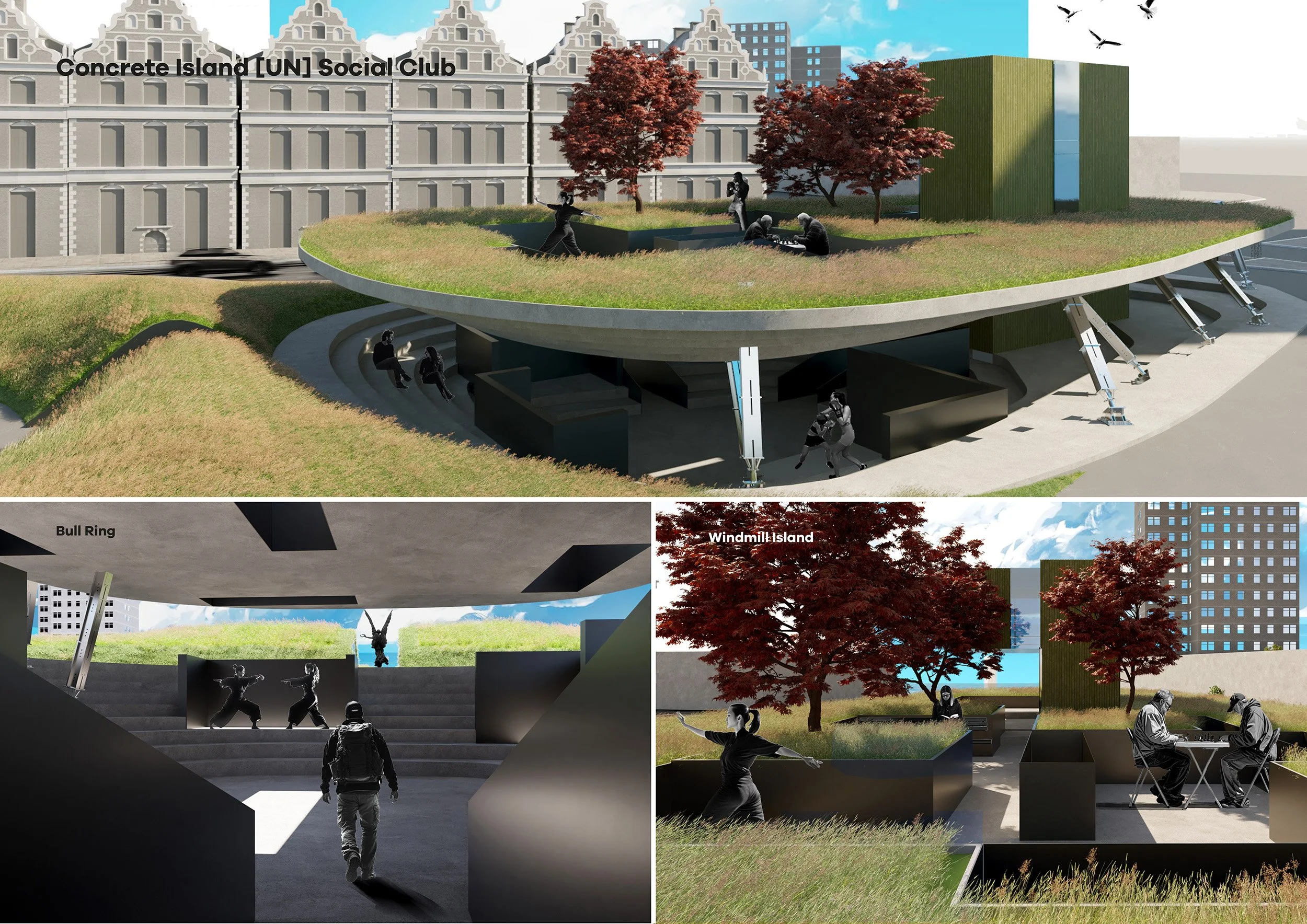

Concrete Island [UN] Social Club

Jacob Low - RIBA Studio Certificate

Personal tutor: Steve Bowkett

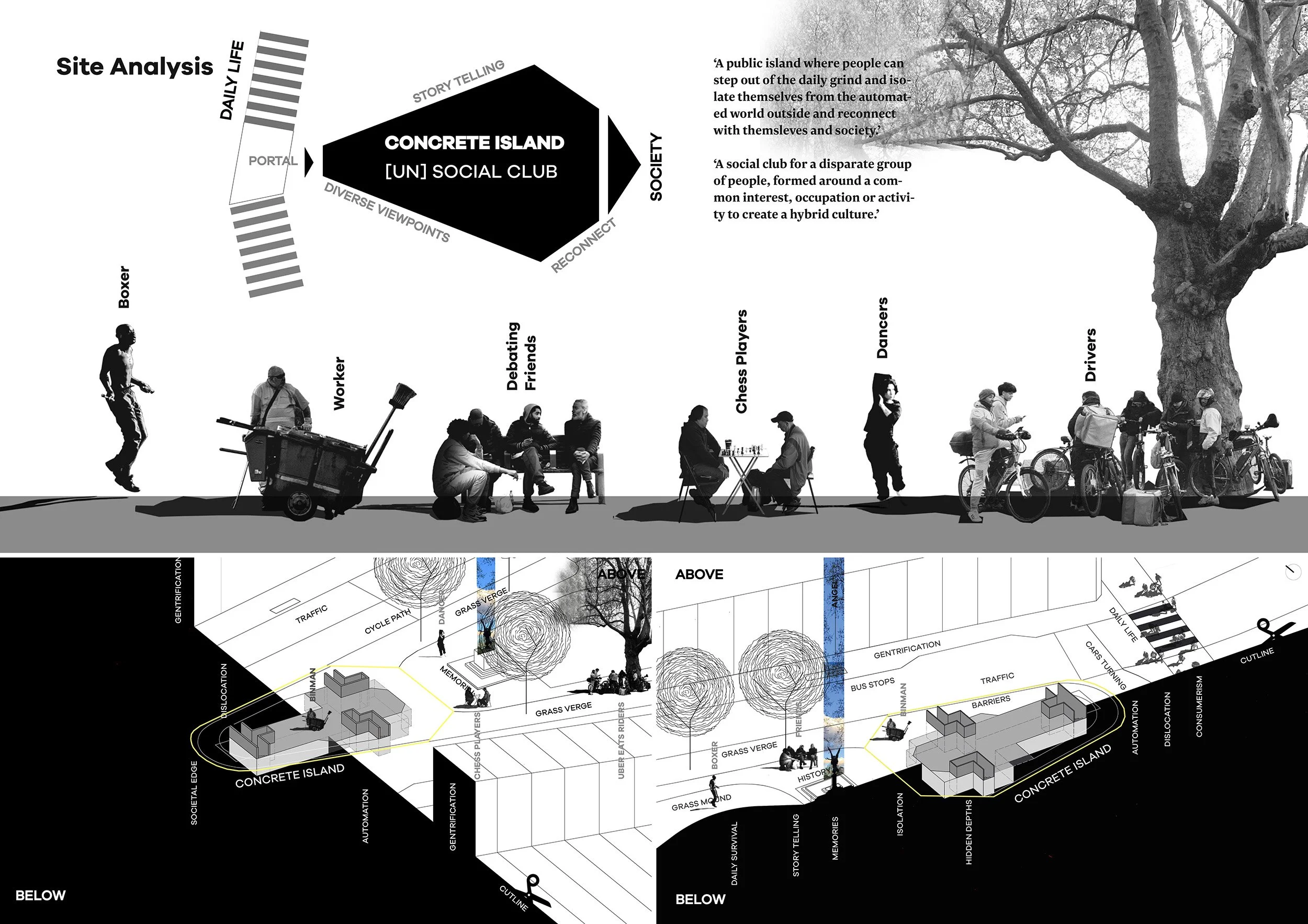

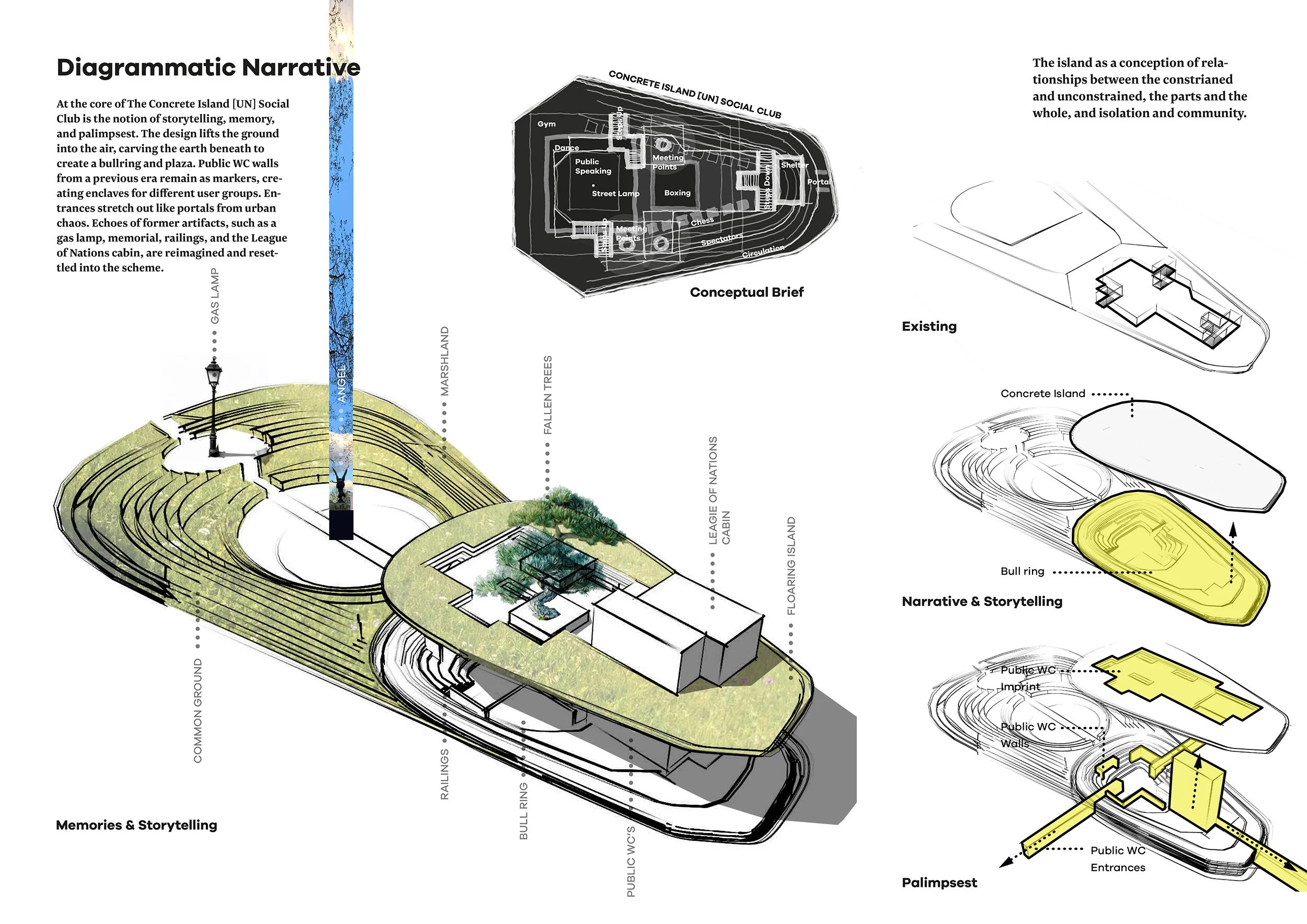

The Concrete Island [UN]Social Club is inspired by the Pelican Stairs in Wapping—a hidden portal within London’s relentless expansion, where the past bleeds through. This project reclaims a forgotten site on Shepherd’s Bush Green, a glitch in the urban matrix. These fissures in the system are realms abandoned yet alive—overlooked remnants of the past against the ever-expanding consumer world around them.

Inspired by J.G. Ballard’s Concrete Island (1974), the proposal reflects the story of Architect Robert Maitland, trapped on a neglected island and forced to reconnect with society.

Crumbling staircases, gas lamps, and tree stumps form traces of lost narratives. Amidst tarmac and concrete, a hybrid culture weaves together commuters, Uber riders, dancers, boxers, and workers inhabiting the city’s edges. This hybrid culture becomes the main character in the proposal.

The site unfolds in layers. At the lower level, the “bull ring” amphitheatre forms raw enclosures from imprinted toilet walls for gathering, debate, and performance. The park level becomes a vibrant plaza alive with chess games, book clubs, and performances.

Above floats the ‘windmill’ island—an introspective space for dance, reading, or quiet meeting. Anchoring the whole is the clubhouse: a vertical spine linking amenities, a community room, and a café lookout nodding to the lost ‘League of Nations’ cab hut which once was there.

The Concrete Island [UN]Social Club reimagines urban existence, blending history and community in a layered public space that invites reflection, interaction, and reconnection with forgotten narratives.

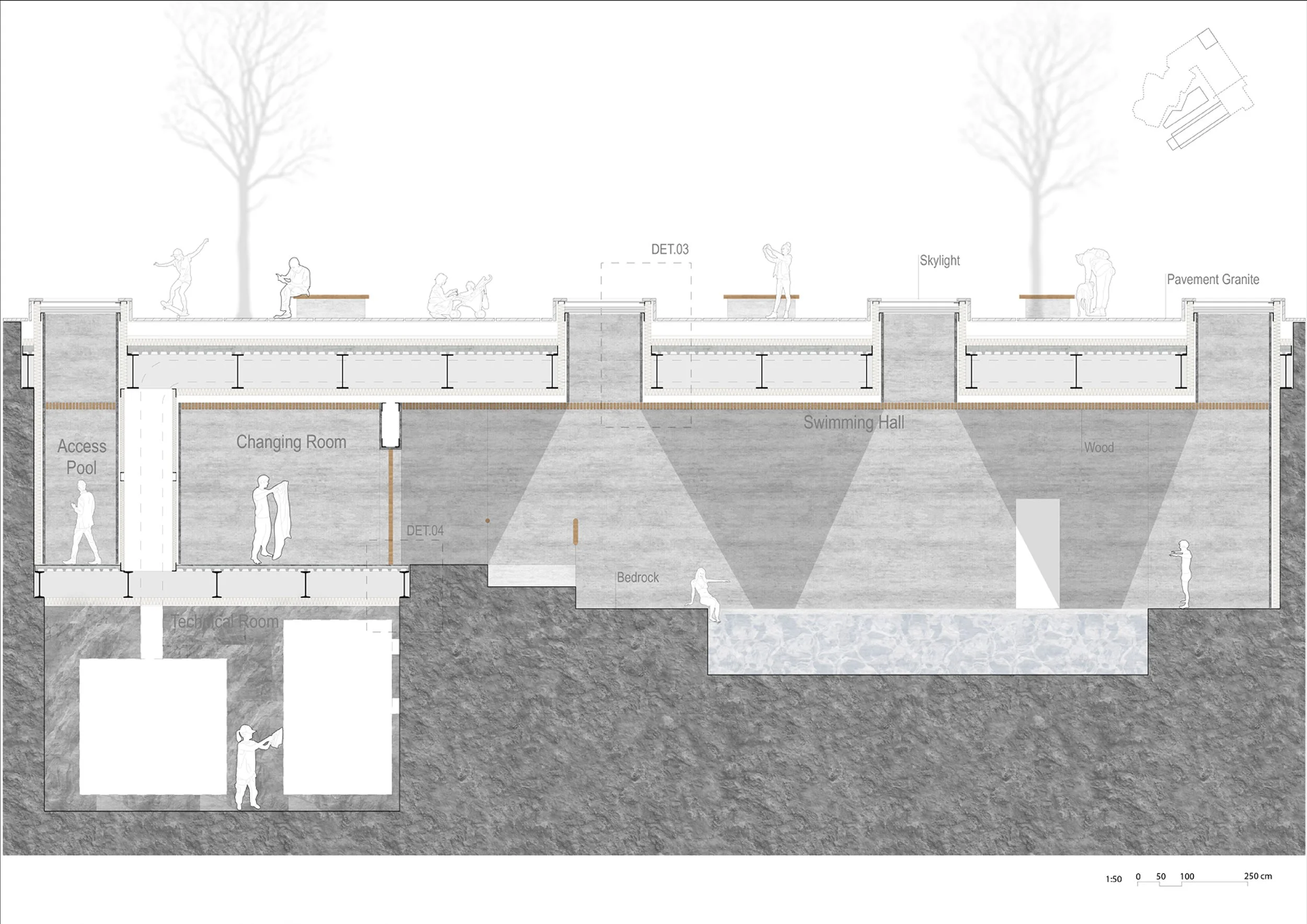

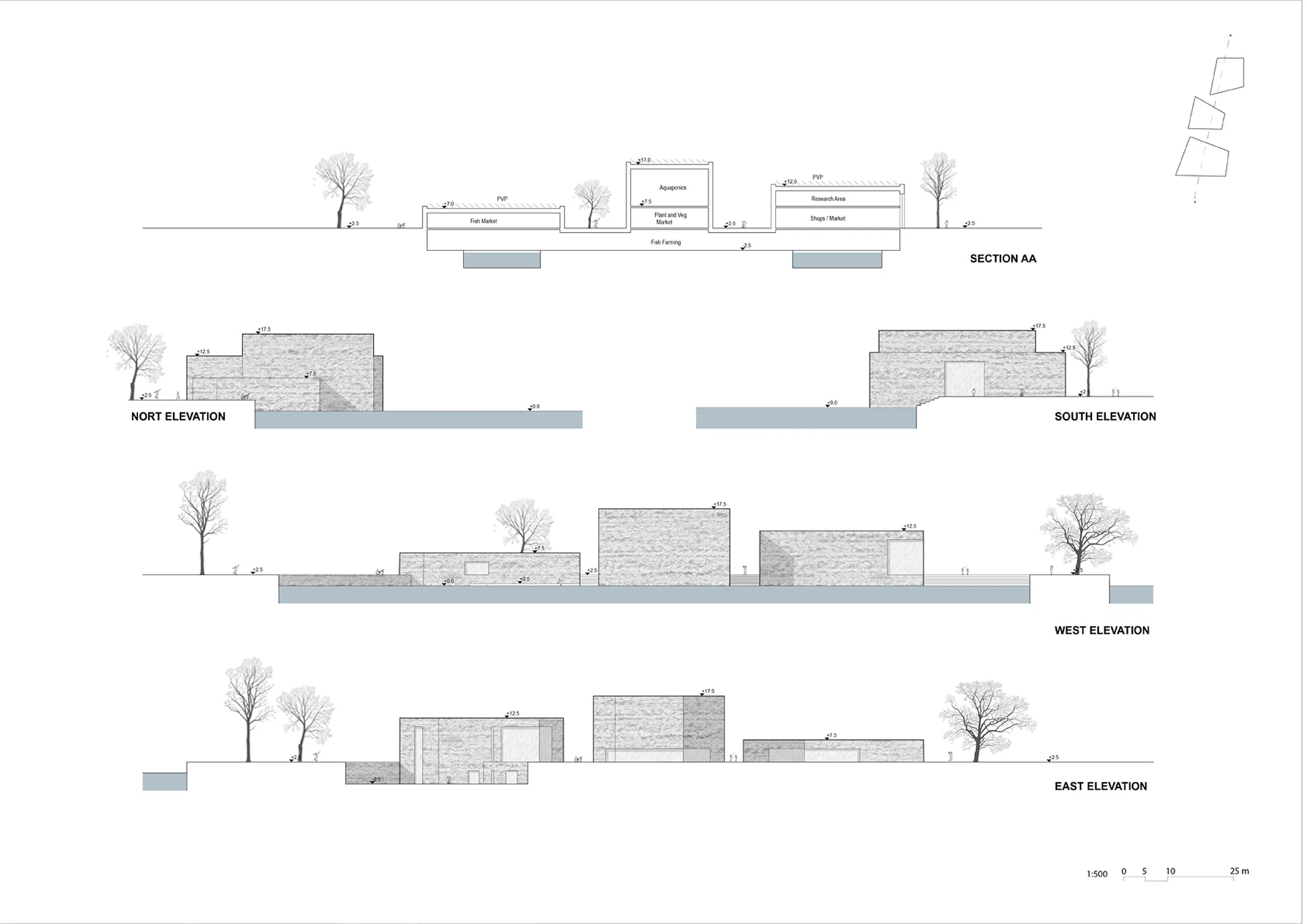

Helsinki New Edge Condition

Bruno Vaz - RIBA Studio Certificate

The design project, "Helsinki New Edge Condition," aims to integrate the countryside into the city by incorporating light-well outcrops that introduce natural light into the excavated areas. This project explores the relationship between granite, water, and natural light, strongly focusing on sustainability and Finland's geological heritage.

The design pays tribute to granite's cultural significance in Nordic prehistory and Finnish romanticism while embracing modern and sustainable practices. It highlights granite's durability, thermal properties, and aesthetic appeal, employing contemporary quarrying and sustainable techniques to minimise environmental impact.

The master plan reclaims the site's historical importance while celebrating Finland's natural landscape. It creates a flexible, year-round environment that ensures accessibility and functionality throughout all seasons. The design features three main spaces: an underground thermal spa, seawater swimming pools, and a sustainable food production farm that offers locally sourced food. A closed-loop system reduces waste, minimises reliance on external supply chains, and decreases the environmental footprint.

By promoting sustainable farming practices and utilising locally sourced materials, the project stimulates the regional economy, creates jobs, and strengthens the connection between the city and the countryside. The interplay of granite, water, and light enhances aesthetics and sustainability. During the day, natural light fills the spaces, while at night, artificial lighting accentuates granite textures, creating an immersive, eco-friendly environment that fosters cultural, ecological, and economic well-being.

HIGH-BRID?

Graeme Williamson - RIBA Studio Diploma

Personal tutor: Ben Stringer

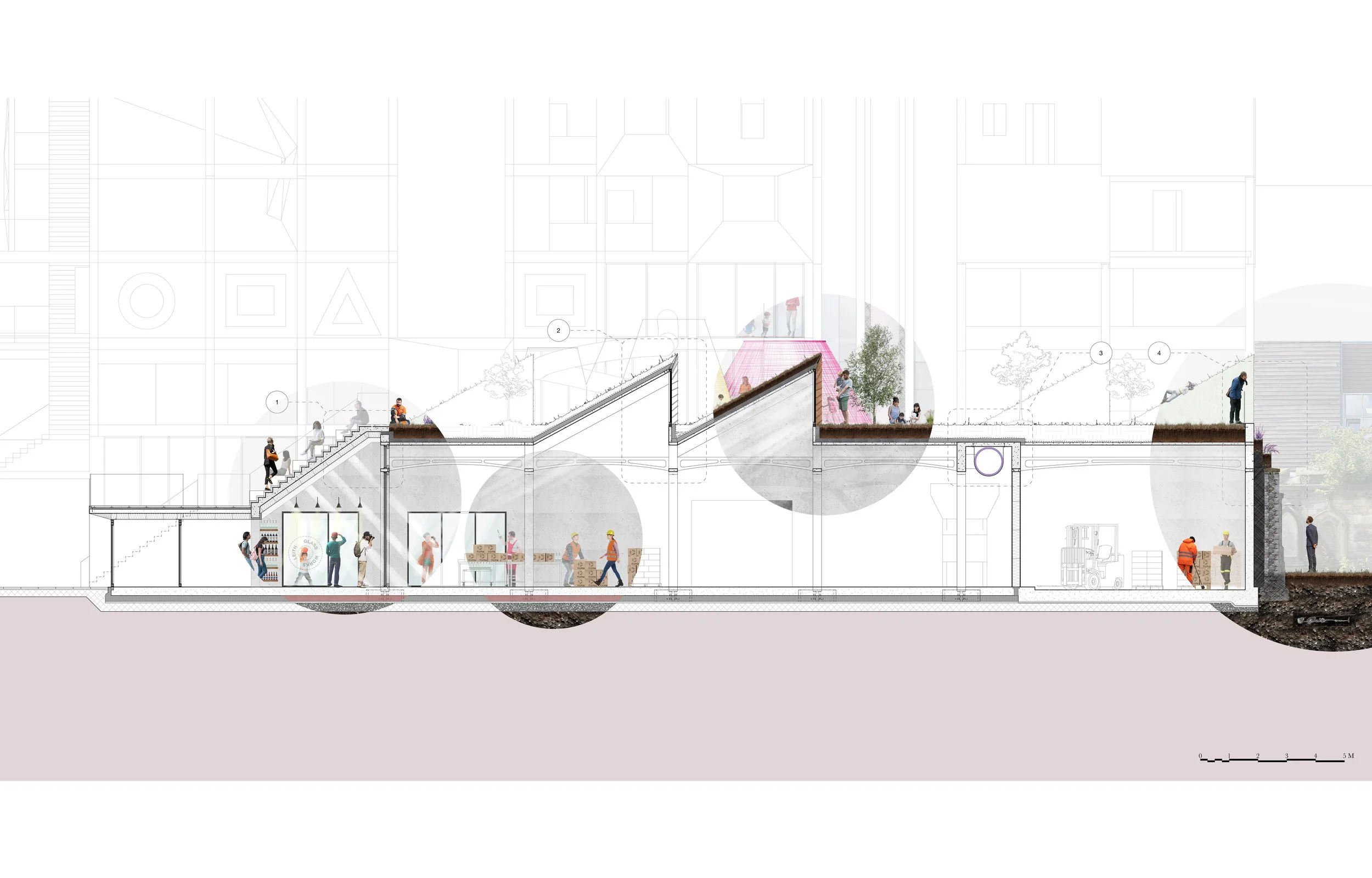

The site is in Leith, Edinburgh’s port, and includes a pedestrianised shopping area and a 17 storey residential tower; an apt location to explore the High-Rise brief. Once a diverse, vibrant and popular destination, the ‘Foot of the Walk’ is now mediocre, and the new tram stop is uninviting.

Four themes undergird the project:

Independence // Connectedness: Leith’s culture of making is re-established and put on display through a public-facing bottle factory and shop. Connectedness to the city is enhanced by overhauling the tram stop - forming a public square and a new thoroughfare. The vast climbing wall doubles as a canvas for local artists to make their mark on the city skyline.

Old // New: A diverse programme of spaces is reintroduced into the site. This hybridity provides opportunities for live, work, and play to happen in close proximity.

Play // Utility: The factory roof, made of concrete for utilitarian reasons, is also sculpted to form an undulating landscape for children to explore. The climbing wall conceals a fire escape and the purple chimneys blend with the coloured chutes and tunnels provided for kids.

Disadvantage // Prosperity: Blue-collar factory workers are placed in the heart of a community amongst amenities and greenery. Their work is in public view, enhancing appreciation for their products. Low-income tower residents now have three additional means of escape. They can also rent affordable work units in the tower, cultivating entrepreneurship.

The scheme offers a richness similar to that which once existed on the site, interpreted for the modern age.

[Untitled], or perhaps, Generation Generator.

James O’Hara - RIBA Studio Diploma

Personal tutor: Toby Shew

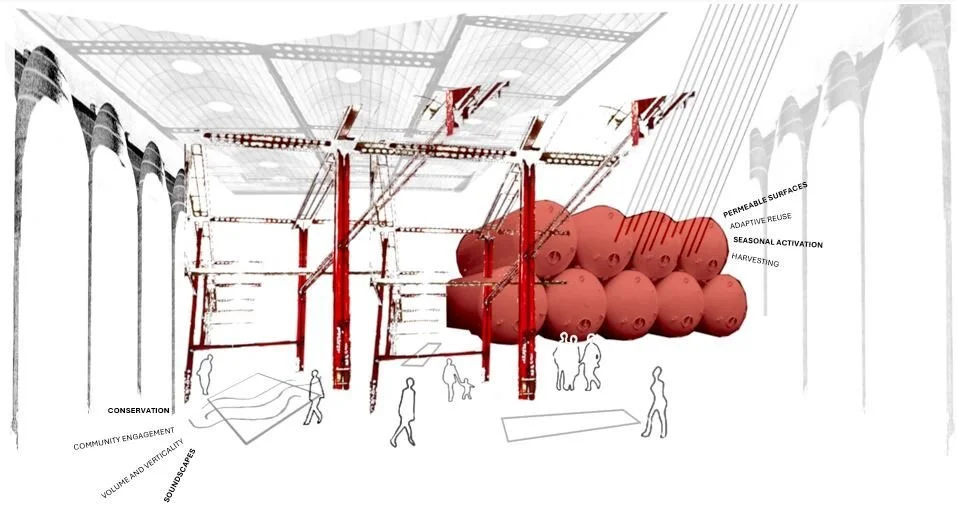

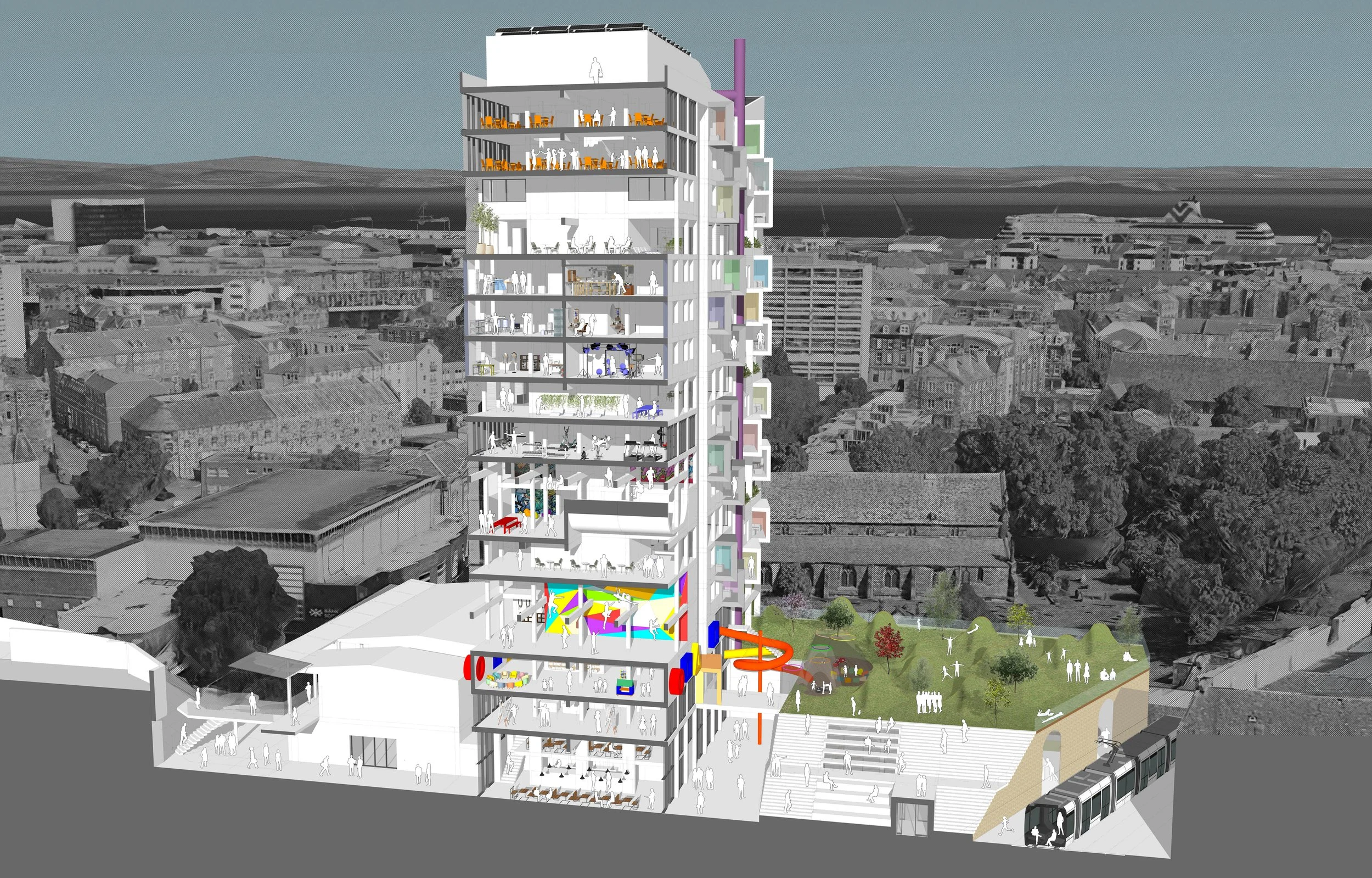

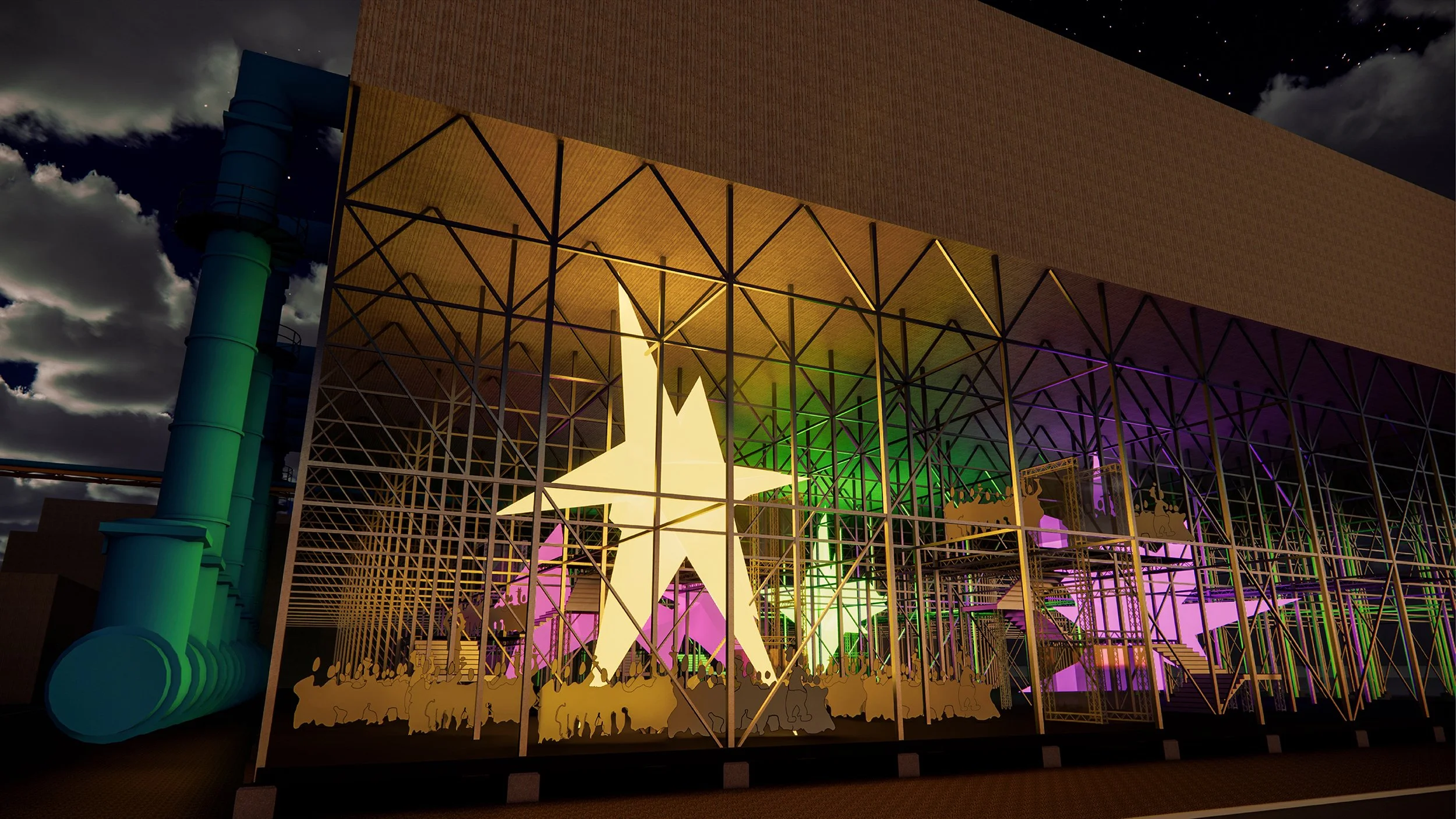

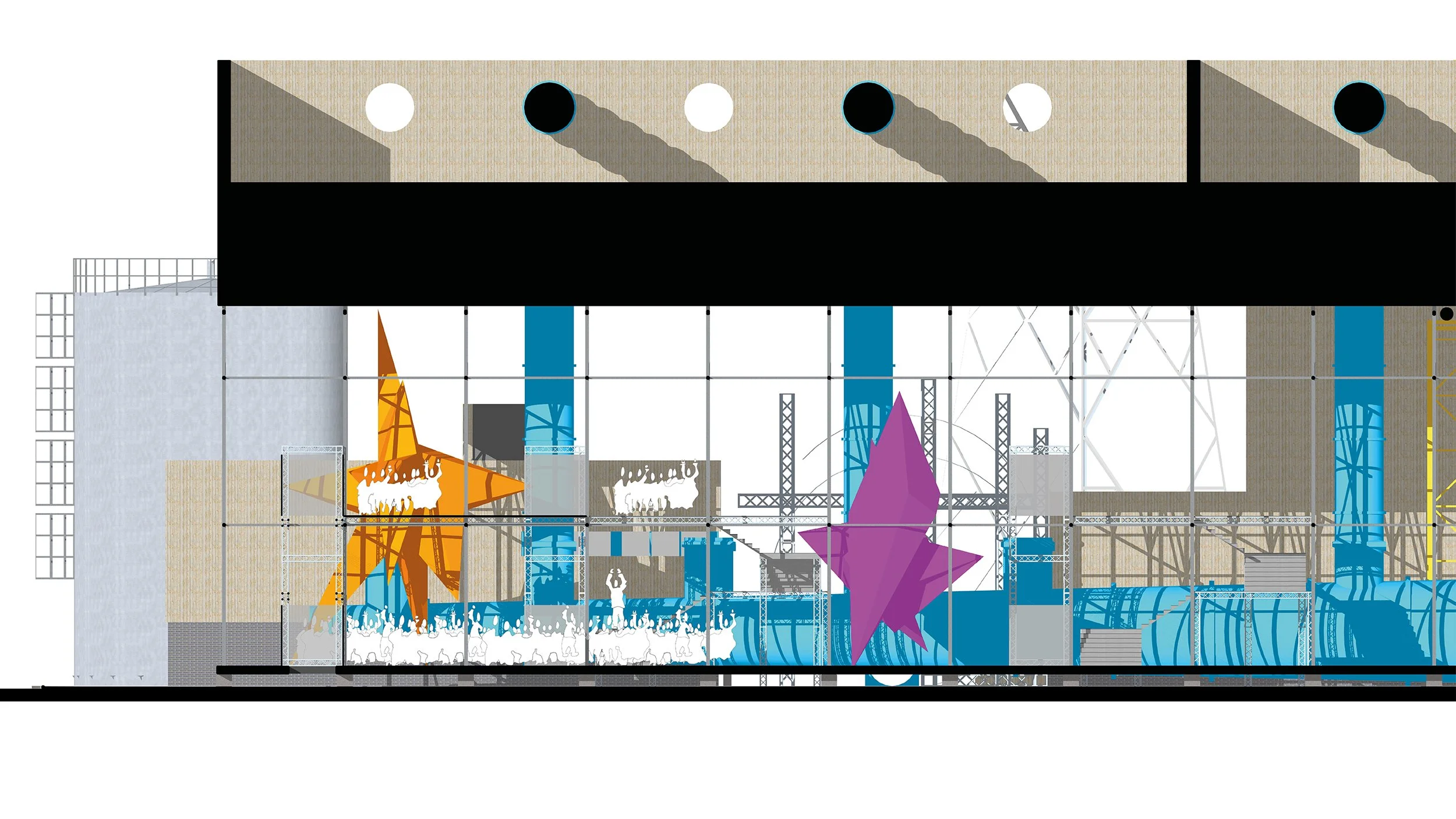

The project explores how a combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) power station, decommissioned in the 2030s, is repurposed in the wake of climate change driven flooding forcing people out of London. As well as architectural precedent, literary and social methodologies are used including near-future science fiction, the D.I.Y skatepark movement and meanwhile-use rave venues.

The project is in part a polemic railing against the redevelopment of Battersea Power Station as high-end retail and residential, but more broadly the subjugation of creativity to commercialism. It postulates a semi-anarchic future where creative communities form a collaborative, sustainable ecosystem extrapolated from present day Community Interest Company models.

The community inhabits and adapts the technologically specific spaces of the former power station. Each chapter builds upon the last. The fabric is at first repurposed ad-hoc during illicit forays within the fence. Successive generations reimagine the works of those who came before, as well as developing systems for externally salvaged materials. The site becomes formalized and integrated within its locality. The architect’s role is as community collaborator, creative curator, construction coordinator.

Salvage DJ Booth Concept

Space Invaders

Space Invaders Event Space

Macro-mindgas

Plaza

Event Space

Space Exploration

The new intake

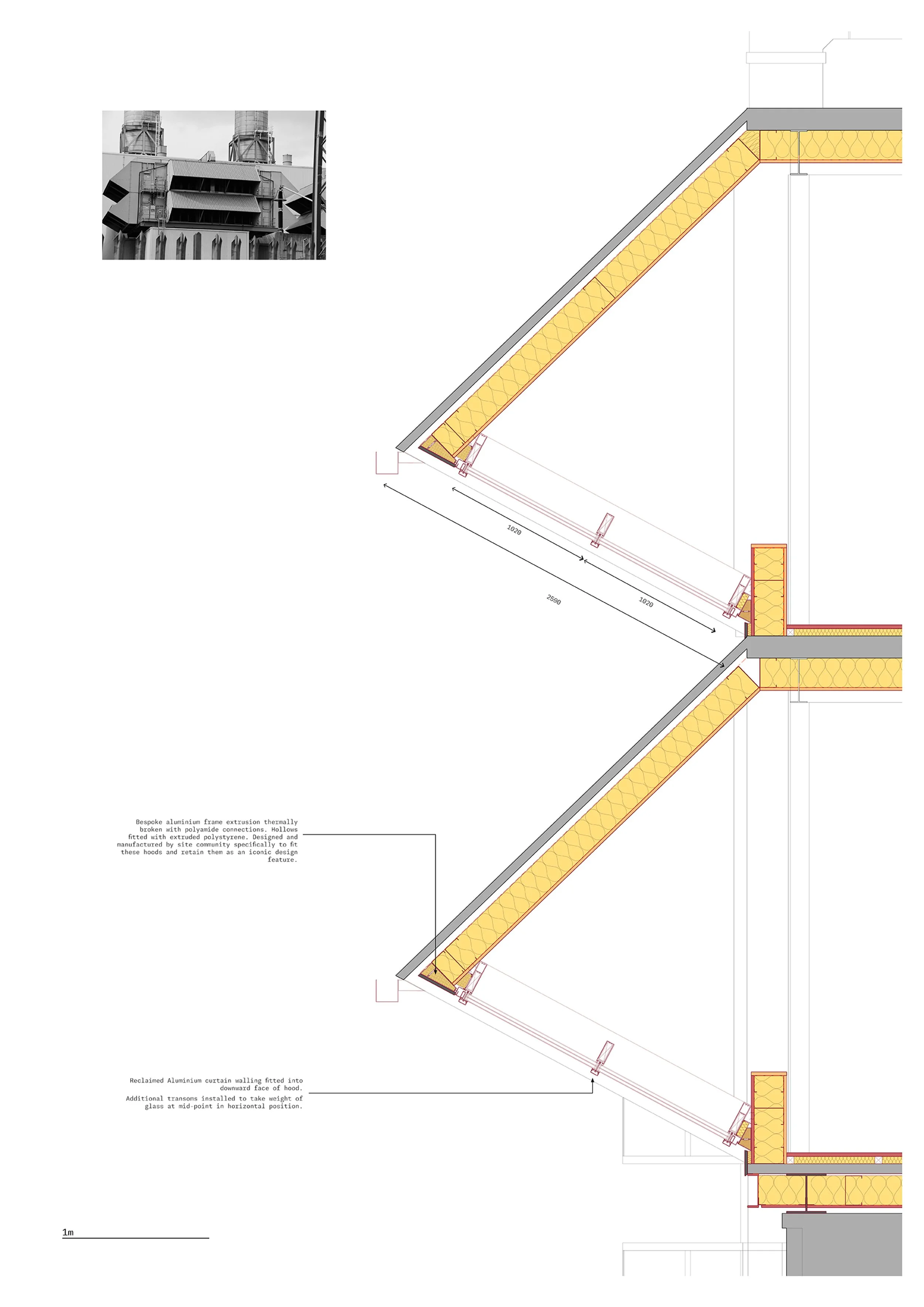

Air-intake workshop (detail)

The Mothership (section)

Fell Hiraeth

Mike Austin - RIBA Studio Diploma

Personal tutor: Michael Spooner

The project is driven by a narrative involving the Forest of Dean Freeminers, who declare themselves Guardians of Earths natural resources, with an Animistic belief that a spirit exists in all things, people, Trees, Earth, & Rock.

They manufacture a pilgrims’ trail, leading to community space for humanity to reflect on their place in the world, and acknowledge the fragility of our ecosystem, without generating anxiety.

But this is just a decoy designed to shroud the true purpose of the project in mystery, with camouflage and distraction.

A hidden Cave, accessed from a disused railway tunnel provides respite for people in positions of power to meet, debate and resolve issues of critical global importance, to reflect and reach agreement in secret, to expedite difficult decisions in relation to Earths precious minerals.

The Cave is central to wider strategies, with sleeping accommodation and relaxation space

nestled amongst the Trees in the East valley hillside adjacent the Tunnel mouth. Built form will prioritise natural building techniques, materials and minimal use of technology.

Zero-carbon lighting and natural ventilation is proposed via Heliostat towers built within the forest, feeding light and air down through ventilation ducts to the Cave below.

Cut section C shaded

Cave cut section A

Debate Chamber

Section looking north

Tunnel Renders

Longditudinal Section 1-500

Models

NE Iso 1-1500

Pilgrims Trail Decoy

Fell Secular Retreat

Charlotte Woodland - Dissertation

Dissertation Abstract: There is a growing awareness of the impact that the built environment has on the health and wellbeing of individuals, in 2023 the World Health Organization recognised loneliness as a threat to public health. This dissertation explores the urban loneliness phenomenon to understand why superdense urbanism fosters the emotional response.

The review of the existing psychological literature on loneliness revealed an under-explored area relating to the individual’s contextual environment. It was also identified that solitude is a closely related emotional state that promotes wellbeing and has positive connotations, in contrast to the negative emotional experience of loneliness.

The discovery of this connection lead to the consideration of architecture which fosters the positive emotional response, the retreat typology. To understand why loneliness is fostered by the super-dense urban environment and how this differs from the solitude experienced in retreat architecture, urban and rural case study examples have been compared and contrasted, to analyse and critique how siting, programme and materiality promote solitude or contribute to feelings of loneliness. The case study analysis has been critiqued against the findings from the literature review and the critique of superdense urbanism.

The findings of this discourse indicate that loneliness is fostered within the superdense urban environment as a result of the highly controlled, highly stimulating and segmented environment, which is thought to neglect the inhabitant’s psychological needs, isolating them from place. From the case study analysis, it was understood that it is possible to promote solitude within the urban environment through establishing a

safe internal ecosystem for the inhabitant that is abstracted from the contextual urban milieu. This contrasts with the nature-based retreat response which integrated the inhabitant in the existing ecosystem, to foster feelings of belonging. In light of this, it was established that the fundamental shortfall of the urban retreat is the delicacy in the human-architectural reconciliation between providing a safe and secure internal

retreat environ, whilst not further isolating the individual from the wider context, which proposes an area for further research.

Key Quotes

“Both fear and loneliness are aversive signals to the human consciousness which result in a behavioural response to keep the social body safe, in the case of fear this could be defined as the retreat to the vehicle or the reduced use of the pavement. In the context of loneliness, the emotional response proposes further complexity. As previously discovered the primitive response to loneliness is thought to have triggered a prompt to re-establish social connections as explained by Bowlby’s ‘attachment theory’.

However, according to theories of evolution, individuals now experiencing loneliness also feel unsafe and as a result develop a hyper-vigilance for perceived threats as explored by Hawkley and Cacioppo. This results in withdrawal behaviour which translates to empty streets and isolation in vehicles.” – P.13

Analysis of Ando’s Azuma House: “The first-floor bedrooms are accessible by an outdoor staircase and are connected by a bridge which establishes further disconnection within the programme. The glazed elevations facing the courtyard heighten feelings of exposure, opposing Appleton’s ‘prospect-refuge’ theory, where one can see without being seen (Pollan, 1997, p.49) (see Figure 35). The mutual overlooking between inhabitants evokes a sense of constant observation, which could be likened to Bentham’s panoptic principles in prison design (Ching, et al, 2011, p.639). The concrete structure forms the intermediate floor, walls and roof, which Unwin notes is the formula for the creation of a room which may be ‘…a place of refuge, solitude, perhaps of imprisonment…’ (Unwin, 2014, p.43) which further compounds the parallels between penal architecture and the cellular bedrooms.” – P.48

“This discourse highlights the ethical responsibility held by architects to address the issue of urban loneliness, and this is summarised by author Jeremy Till’s analogy of metric scales representing the ratio of architect to society, 1:100 symbolising, one architect to one hundred people or one hundred points of view, when increased to city scale representation, 1:10,000 suggests that it is necessary for the architect to ‘…come down from on high, both literally and metaphorically, and to listen to the voices coming up.’ (Till, 2009, p.179). In conclusion the design of super-dense urbanism should involve architects committed to the wellbeing of the end inhabitant and include consultation with diverse demographics to create environments that address the psychological needs of the end user.” – P.68

“Loneliness is understood to be a deficit condition, and this could be caused by the disconnect between people and their optimum habitat, creating a form of ‘environmental loneliness’ in city dwellers that can only be resolved by spending time in nature. This offers an explanation for Laing’s relief when outdoors, suggesting that proximity to nature and optimum habitat could be a remedy for urban loneliness. It is however difficult to establish this connection within the context of the city as identified by Field, ‘urban nature’ is a contemporary construct, resulting in curated green spaces that fail to reflect untouched nature. Paired with the perceived threat in the urban environment, the urban retreat response is to form a self-contained ecosystem, prioritising safety and withdrawal, as demonstrated by the case study examples. This establishes a greater sense of belonging and connection by creating an internal personal space. However, this could simultaneously foster an estrangement from the wider urban context, as described by Relph, potentially exacerbating feelings of loneliness.” – P.37

“The urban retreats connect to the wider city context through the use of man-made materials, which could contribute to feelings of isolation and loneliness through bringing elements reminiscent of the wider context into the individuals personal space, heightening feelings of perceived threat. However, this could also reduce feelings of ‘existential outsideness’ as discussed by Relph. Familiar materials could be recognisedin the wider context outside of the retreat which may aid in reduced feelings of alienation when the inhabitant ventures outside. In the same way, Chang’s integration of the bench seat, representative of chairs on the train, may also draw connections to the wider context of the city, without the connotations of danger as the inhabitant is within the safe internal retreat environ and has a lower sense of perceived risk due to the safety and security established. The inclusion of familiar stimuli may disturb the solitude as described by Schools or could reduce feelings of existential outsiderness by creating a parallel familiarity with the wider context.” – P.65

“The findings of this dissertation suggest that the urban milieu could be adapted to transform urban isolation into an opportunity for positive social withdrawal, promoting solitude and a deepened sense of belonging. The research suggests a nuanced approach that incorporates natural materials and establishes human-architecture reconciliation through autonomous spatial design could establish an equilibrium between solitude and social-connection, allowing urban retreat architecture to address loneliness rather than amplifying it.” – P.69

Analysis of Zumthor’s Secular Retreat: “In urban settings, as identified by Ando, large expanses of glazing increase feelings of vulnerability but here they promote solitude and enhance feelings of ‘refuge’ through the observation of the elements from a position of shelter. Although the retreat has a fixed programme, autonomy is still promoted through the incorporation of private and semi-private spaces. Inhabitants can gather to socialise or retreat to private rooms for solitude. Carefully placed ‘dwelling spots’, such as chairs and desks face the view and create intimate spaces within the larger scale of the retreat, promoting reflection and connection to place (see Figures 32,33). These spots align with Pallasmaa’s idea of dwelling fostering a sense of belonging, while also reducing the double height space to human proportions, aligning with Yudell’s observations of human scale promoting connection to place.” – P.44

“It was recognised that the nature-based retreat response was to establish a deep connection to the environment, addressing the individual’s estrangement from nature through integrating them in the existing ecosystem, promoting feelings of solitude and belonging, even when the inhabitant is physically alone. It was also understood that autonomy and solitude were closely related, and this was reflected in Schols’s cabin ANNA and Zumthor’s Secular Retreat, which permit the inhabitant to adjust their surroundings to meet their changing needs. The nature-based retreats evidence human-architecture reconciliation through mindful design and establishing connections to the contextual environment. In contrast, the urban case studies evidence that solitude could also be achieved in the urban context. It was discovered that to promote solitude the urban retreat must distance the individual from the perceived threat of the city, through establishing a personal internal ecosystem, which differs from the nature-based retreat response. However, it was considered that this can heighten feelings of ‘existential outsideness’ as discussed by Relph. This highlights the importance of reconciling the safe internal retreat environ with a sensory disconnection from the city, that promotes solitude without further isolating the individual from the wider context” – P.67

Secular Retreat Dwelling Spot 1

Secular Retreat Dwelling Spot 2

Secular Retreat Plan Analysis

Secular Retreat Sketch